One of my favourite things to do as a child was nosing around Ama’s drawers in her massive bedroom. I was about 8 or 9, living in Taichung, Taiwan. My parents and my brother lived on the fourth storey of a low-rise building Ama owned, and she occupied the third floor. This is the same building my Ama had raised her children–my Baba and his older sister and younger brother. On the weekends, I headed downstairs to spend time with my Ama, who was my favourite person at the time. While she watched the television, I opened all her drawers and boxes, digging for treasure. There was one object that held my attention: an aurora borealis bead necklace made of sparkling, multi-faceted Austrian glass. When Ama wore it with one of her pretty floral dresses, the necklace glistened in a spectrum of light, radiating rays of pinks, yellows, and blues. I thought it was the most glorious thing in the world. When I pulled it out of one of her jewellery boxes, I held it up to her. “Ama, can I have this?”

“You can have it when you grow up,” she said as she took the necklace from me.

Three decades later, I found myself in Ama’s room. It was late at night, and I snooped around her drawers, as I had done when I was a little girl. Since the autumn of 2019, Ama has been living in a nursing home where she can receive full-time care. When Derek and I visited for Chinese New Year’s, we stayed in her room. It felt surreal to be in the place I had spent so much time. So much has changed–I am no longer a child, and my relationship with Ama had hardened over the years. As a little girl, I idolized Ama. Even after we left Taiwan, I was still close to her–Baba had found a stack of letters I had written to Ama from my first couple of years living in Canada. However, the physical distance had taken a toll. As I became more westernized in my behaviour and thinking, Ama ceased to be important in my life. Then, in my 20’s, our relationship took a turn for the worse.

As a young adult, every time I’d visited Taiwan, Ama was critical of me. The minute she laid her eyes on me, she tsked. “How did you get so fat?“

I was already subconscious about my body, and though I am sure she didn’t mean to hurt my feelings, she did. She was also unkind to Mama, which upset me. I witnessed many times when Ama belittled her cooking, commented on her appearance, and said unflattering things about her family. For many years, I was angry at Ama. Despite my animosity, I made annual pilgrimages to Taichung during Chinese New Year’s. Each year, I bore Ama’s verbal lashings and thought that I was doing it out of my love for Baba. Lately, I am starting to think that maybe it wasn’t just for Baba, after all.

As Derek snored in Ama’s queen-sized bed, I opened one of the drawers. It was jam-packed with stacks of papers–electricity bills from the ’80s, old bank statements, receipts from a doctor’s visit. I opened another drawer and found a round, plastic orange box commonly given away by jewellery stores in Taiwan. Inside, glistening beautiful vintage rings of jades and pearls with unique settings that are no longer in production. Then I found a bottle of Rémy Martin XO Cognac, a pair of diamond studs, a red envelope filled with 10,000 NT (about $330 USD). I had forsaken sleep and was driven by an obsession to open more drawers and cupboards. I peered at old letters and photographs, flipped through ancient address books and notebooks, and found many old fashioned brass keys that no longer open any doors. The more I discovered, the more insatiable I felt–subconsciously, I was looking for one thing–the aurora borealis bead necklace. As dawn drew near, I gave up my search, laid down next to Derek and slept.

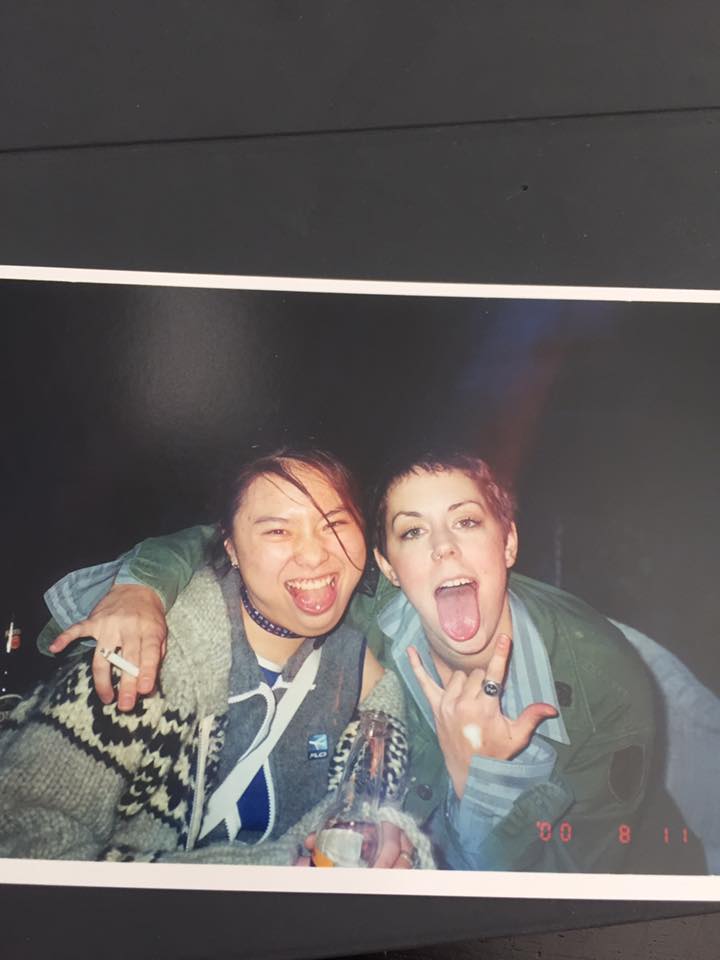

The next day, I poured over the letters and the photographs. Old love letters she wrote my grandfather that she probably never sent. Black and white photos of relatives that I never met. Through her things, I got to know a side of Ama that I had always known but forgotten. Perhaps I am not so different from her after all–my obsessive need to hang on to memories is not too different than Ama’s. Instead of keeping every scrap of paper, I store my thoughts and sentimental objects in my notebooks, which I have done since I was 13. Ama and I are both hoarders in our own right. Unlike her, I don’t have a house to put away my memories. However, I do keep a box of bound journals that I lug around the world–my life in words and images for the past 25 years.

My resentment towards Ama has thawed, exposing the tender feelings underneath. Though I was embittered for how Ama treated Mama and me, deep down, I was always looking for Ama’s aurora borealis bead necklace. A few years ago, I found something similar when I was living in Savannah, GA. I bought the necklace without thinking twice. Now, I know that I have always wanted to be close to Ama, whether or not I wanted to admit it. During my last visit to Taichung, I visited Ama in the nursing home. I held her hand and spoke to her, even though I knew she couldn’t hear me. I was sorry for the wasted time, all the years I could have asked her about her youth, what her dreams and aspirations were, and why she chose to be with a married man for all of her adult life. But I didn’t. Now, I can only get glimpses of who she was–filtered through her pictures, words, and possessions. I suppose that is better than nothing.

Edited by Mohini Khadaria