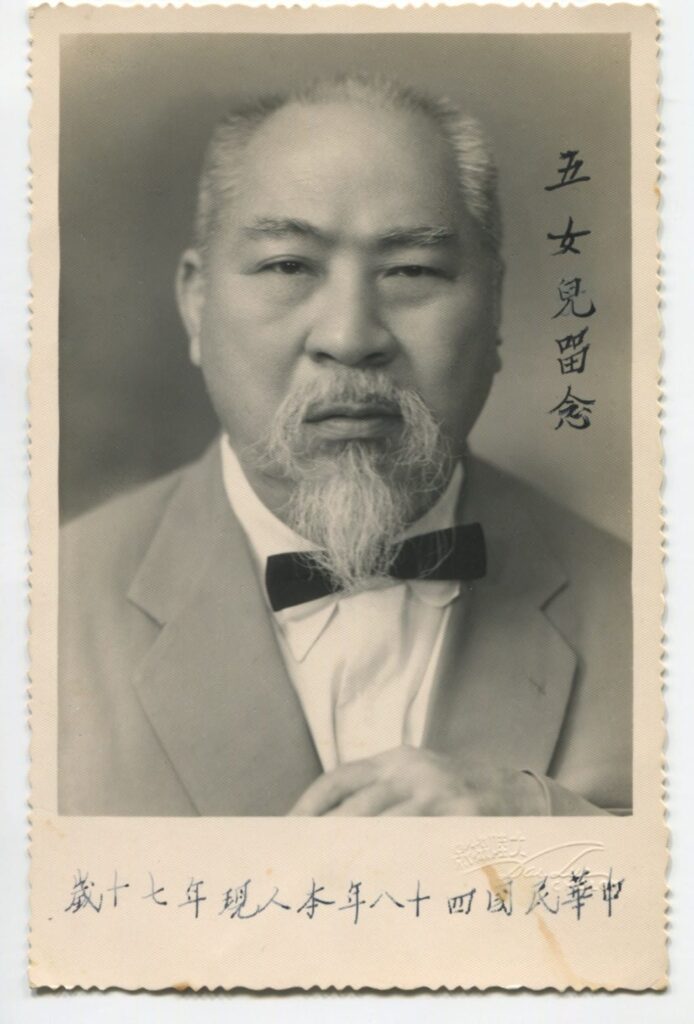

My grandfather, who I called Agon, was a sentimental man. When he went on a whirlwind tour around the world in 1964, he sent Ama ten letters and postcards. Even though I haven’t found all of them, I know that he’s visited Greece, Switzerland, Spain, Germany, Argentina, the United States, Thailand, and Japan. He filled blue aerogram letters with his observations of the places he saw, his thoughts, and his affections for Ama and their children.

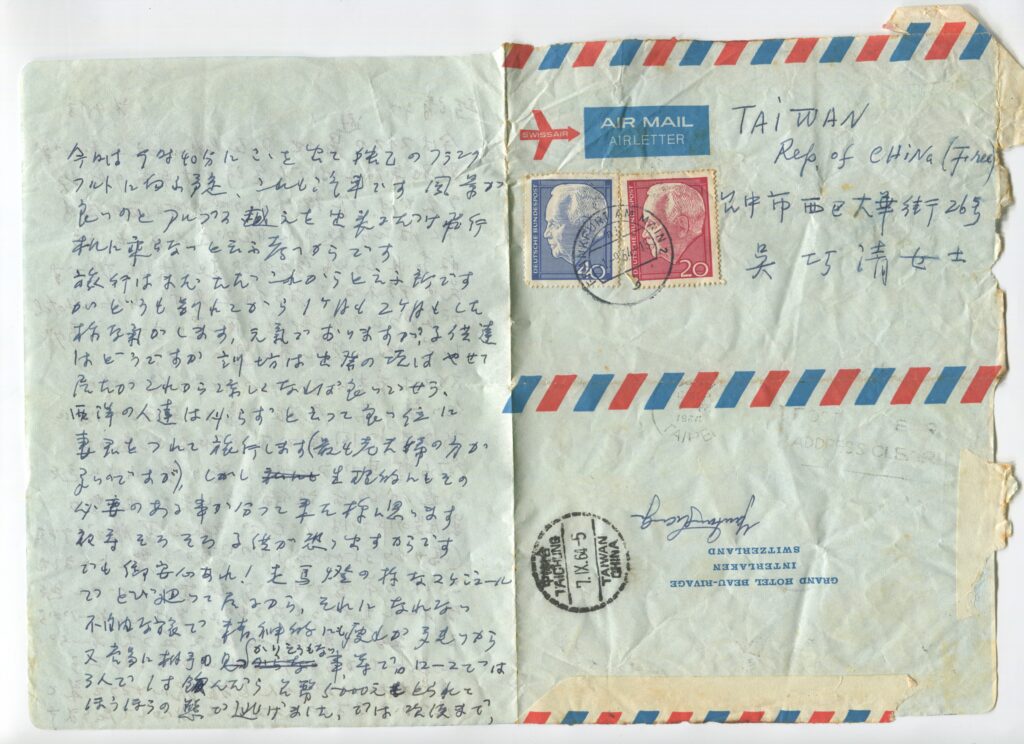

I couldn’t read the letters—Agon wrote in Japanese in his messy doctor scrawl, barely legible even to my aunt, who spent most of her adult life in Japan. I enlisted Aunt Lily’s help because she speaks and reads Japanese. Another reason I had chosen her to share my Agon’s letter is because her family came from Guangdong Province, specifically from Chaozhou— like Ama’s family. Her grandfather and father knew my Great Grandfather. When I showed her the letter, she was charmed by Agon’s long letters that travelled around the world to reach his love over half a century ago. We picked a random letter—the one from Switzerland.

Agon started the letter by describing his travel in the Alps as he enjoyed the views of red-roofed houses and the verdant mountains. He said he was cold—Agon left Taiwan in the summer, and by the time he arrived in the Alps in the autumn, he was still wearing a short-sleeved shirt when it was only one degree Celsius. He also mentioned leaving a book he purchased in Hong Kong in a car in Geneva. Then, he contemplated whether or not he should fly or hire a car to Frankfurt— should he get there as quickly as possible or enjoy the slow ride through the Alps? I assumed he took the car since he wrote about the scenery at the beginning of the letter. Then, he asked about my uncle, my dad’s younger brother, who had just been born before Agon’s around-the-world trip. Agon also mentioned that he felt mentally drained. He said even though it was common for westerners to take their wives on vacations, he felt ill at ease. He didn’t clearly state that he was travelling with his wife, though I assumed he was. It was an implicit way to tell Ama that he missed her.

The following letter Aunt Lily and I looked at together was from Spain. Agon said that it was hot there, like in Taiwan. “I left Taiwan for one month now. I am heading to Argentina tomorrow,” he wrote. “It’s nine p.m. here, which is the afternoon in your time zone.”

There is a mystery in the letter that Aunt Lily and I tried to figure out. Agon asked Ama to reach out to an uncle (舅舅) in Hong Kong (Aunt Lily and I assumed it was Ama’s oldest brother he was referring to since he was the only person we knew for sure that lived in Hong Kong). Agon wanted Ama to contact this uncle so he could visit Ada Ng, who was studying in California—he included Ada’s address in the letter. Agon provided explicit instructions on how to write on the envelope correctly. I don’t know who Ada Ng was, but “Ng” is the Cantonese pronunciation of “Wu” (吳), and so I assumed that it’s most likely Ama’s cousin since they share the same family name. Perhaps it’s Ama’s brother’s daughter—maybe I need to ask my father. Agon closed the letter by telling Ama about the beautiful ladies who looked oriental. “But seeing beautiful Spanish girls made me think of you,” he wrote.

From Argentina, Agon wrote about the best steaks in the world and noted that since Ama didn’t eat beef, she probably wouldn’t be envious, but their children would be excited. He also discussed the Asian stock market and when Ama should sell her stocks. Then, he inquired about the house they were building together, which is the house I’m living in almost sixty years later. Agon said he would like to live on the second floor of the new house but deferred all other decisions to Ama. Finally, towards the end of the letter, Agon wrote about an event he was attending in which he represented the ROC—it’s unclear if it was a medical conference in Argentina or the Tokyo Winter Olympics.

In the letter from California, he talked about how the city was hot but cooler by the sea. He told Ama that he had prepared a gift for Ada—a watch purchased in Switzerland. However, he didn’t mention the visit with Ada, which I found curious. He also talked about women in this letter and said that the Californian girls were the prettiest ones in America. Agon said he would fly to Tokyo the next day to attend the Olympics and return to Taichung in late October. He asked Ama to be patient. He closed the letter by indicating that he had grown weary that airports and hotels had become his home.

Aunt Lily and I only looked at a few letters that day and not in chronological order. Agon was so warm and affectionate in his letters. He wanted her to see what he saw and document his thoughts. I imagine him stealing a moment away from his wife as he had a nightcap at the hotel bar, where he revealed his true feelings to Ama.

In understanding some of the content in my grandfather’s letters, I know there was genuine love between my grandparents even though they weren’t married. Even though Agon was married to another woman, and it was his wife that he took on this tour around the world, Ama had his heart. I wish I knew how Ama felt and what she thought—she was taking care of a newborn and building her new house while her man was on the other side of the planet with another woman. Why had he left Ama for so many months shortly after she gave birth to my uncle? I wonder if Ama was bitter and resentful and, at the same time, felt lonely and missed Agon desperately, even though she would never admit it to anyone, not even to herself. I suppose I may never find the answers to my questions though it’s fun and at times overwhelming to imagine the romance that took place two generations ago.