My family moved to Canada when I was ten. We settled in Surrey, which is a sprawling suburbia about an hour from Vancouver. I didn’t speak a lick of English, but luckily, I didn’t pee myself when moving to a foreign country this time.

When we arrived, Baba had to come up with new names for my younger brother and me.

He gave my younger brother the option of “David” or “Davis”. The little eight-year-old boy chose “Davis,” so Davis he became.

With me, Baba said that I should be “Kayo,” the Japanese pronunciation of my Chinese name. I wanted a fancy English name like Davis, but Baba was persuasive. So, Kayo I remained.

However, when I got to school, the other kids butchered my name. They called me “Kay-yo” when it was supposed to be “Ka-yo”. I tried to correct them with my limited English but to no avail. So, “Kay-yo” I became. Now, everybody calls me Kayo, even my parents.

Remember that Day-O Banana Boat song? My classmates used to sing their adapted version: “Kayyyy-yo! Kayyyy-yo! Daylight comes and me wanna go home!” My face would go beet red and they would howl with laughter. I hated that song.

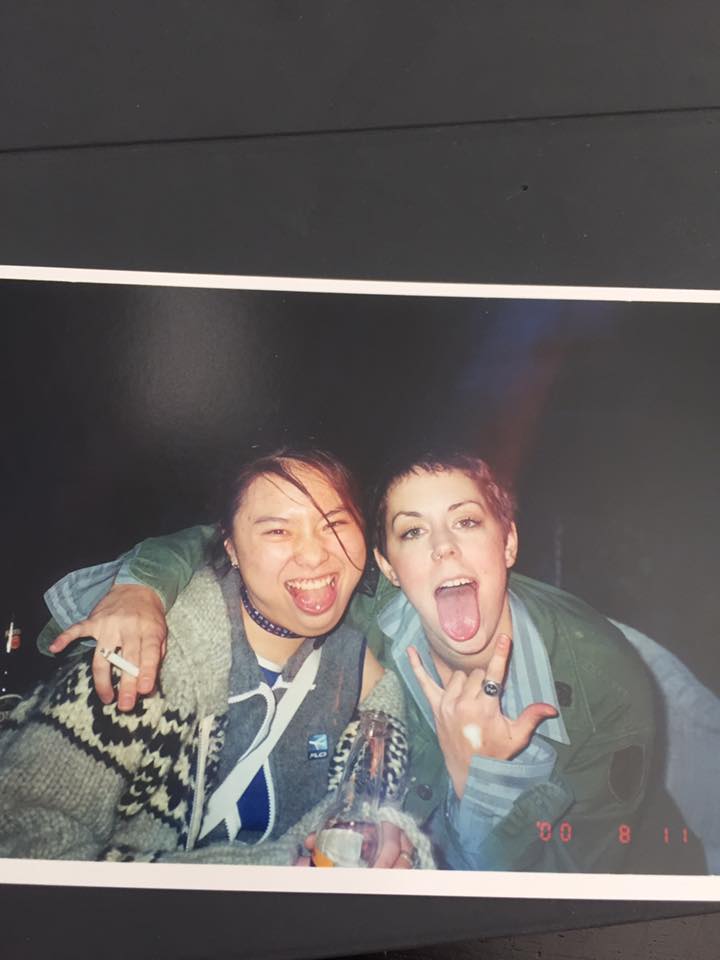

Despite that, I learned English and became a typical teenager. I met my friend Chelsea in a math and science split class in grade eight. On Sundays, we went to the flea market to look for Sailor Moon Cards. In grade nine, I bought my first CDs: No Doubt’s Tragic Kingdom and Smashing Pumpkin’s Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. I saw Gwen Stefani when No Doubt was touring with Weezer—I was a very excited fourteen-year-kid.

In grade ten I smoked my first cigarette. By grade eleven, in addition to my smoking, I also had (still have) a book addiction. Remember those Scholastic catalogs we used to get from school? Mama bought me anything I ever wanted from it, unknowingly created a book-devouring monster. To pay for my smoking and book habits, I got a part-time job at the cinema that opened the same day as Star Wars: Phantom Menace. I made friends outside of school. I met my first boyfriend.

Luckily, the kids in secondary school didn’t sing the stupid Day-O song. Instead, Chelsea gave me a cool nickname: Knock Out, aka KO.

Everything was trucking along in my teenage life. I almost felt cool— until a new Taiwanese kid moved to my school. His name was Rodney.

Every time Rodney saw me walking down the hallway with my friends, he greeted me in Mandarin. I was mortified each time. I always replied to him in English and kept the conversations as short as possible.

He reminded me of my foreign-ness, my otherness— and all I wanted was to blend in, be like everyone else.

I avoided him at all cost.

Back then, I didn’t want to be Taiwanese or Asian. I tried to minimize any perceived differences between my friends and me. For instance, I refused to bring Taiwanese food to school for lunch. Instead, I ate the mush and Jell-O at the cafeteria or munched on chips from the vending machines. Also, I wouldn’t associate with Rodney or the other Taiwanese kids. They thought I was a snob and called me a “banana”—yellow on the outside, white on the inside.

I realize now that I’ve carried that label around for most of my life. The first time my husband Derek went to Taiwan with me for Chinese New Year’s, he asked me why I wasn’t in the kitchen learning to cook all the amazing Taiwanese dishes Mama was making. I shrugged. Now I understand that underneath the exterior of the worldly 30-something Kayo, there is a teenaged Kayo who felt humiliated by her otherness. Buried even deeper is the ten-year-old Kayo who was taunted because of her weird name.

Perhaps this why I get upset when people only see my Asian face and not my Canadian-ness.

Derek suggested that my Canadian-ness is keeping me from my Taiwanese-ness. He is absolutely right.

I will not subject myself to this “banana” label anymore. Next year, I will be in the kitchen with Mama during Chinese New Year.