Originally published in Consequence Volume 15.2 (November 2023).

I couldn’t stop consuming news about Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022. It was political theatre: Beijing threatened Taiwan with sanctions and military action; Washington maintained its commitment to the One China Policy while celebrating Taiwan’s democracy. Meanwhile, in Taiwan, people ate their braised pork over rice at local diners, and the TV showed news clips of Pelosi shaking hands with the Taiwanese president, Tsai Ing-wen.

After Pelosi’s departure, the Chinese military shot missiles into the Taiwan Strait. Some landed twenty kilometers (12.4 miles) off the coast of Taiwan. When reporters interviewed Taiwanese residents about the military exercises in the southern city of Kaohsiung, they shrugged. Some said they went to work, and others claimed they took the ferry for their weekend getaway to Luiqui, the idyllic island known for its sea turtles.

I want to think I’m just as carefree about the impending invasion, but the truth is I’m panicking—as a Taiwanese Canadian woman married to an American who lived in Hong Kong for eight years, I have reasons for concern. The Taiwanese had indeed lived with the constant threat of Chinese aggression since 1949, when Chiang Kai-shek and the then-ruling party of Kuomintang (KMT) retreated to Taiwan after losing the Chinese Civil War. In Chiang’s lifetime, he vowed to take back the motherland from the “communist thugs” while ruling Taiwan with an iron fist. However, towards the end of the twentieth century, many countries began to recognize the Communist Party of China (CPC) as the legitimate ruler of China, and therefore, the United Nations suggested dual representation—allowing both Taiwan and China to be a part of the UN. However, Chiang withdrew from the intergovernmental organization, effectively removing Taiwan’s participation in global affairs. Thus, 1971 was the year China joined the UN, and Taiwan lost its status as a country.

The cross-strait relations between China and Taiwan have always been contentious, and they escalated under Xi Jinping’s leadership. Xi declared that “reunification” between Taiwan and China must be fulfilled and that Beijing may use force if necessary. However, many of us in Taiwan, myself included, have no desire to be ruled by a government with a dismal human rights record, known for imprisoning Muslim minorities and crushing a democratic movement in Hong Kong.

In 2019, while most Taiwanese watched the news in horror as militarized police brutalized young Hong Kong protestors, I lived in the midst of it.

§

I attended the Tiananmen Square vigil on June 4, 2019—the only annual event commemorating the 1989 massacre in Chinese territory—not knowing it would be my last one. After the serene candle-lit ceremony to remember the democracy-seeking Chinese students who died at the hands of the People’s Liberation Army, people began walking from Victoria Park through Wan Chai. They ended up at the Legislative Council Complex, about four kilometers (2.5 miles) away. This was the start of the 2019 protest movement—almost every week from then on, a protest happened every weekend. I could see the procession from the window of the Wan Chai apartment I shared with my husband, Derek. One day, we decided to join them. We donned black t-shirts and marched the streets with Hong Kongers—young and old, students and professionals, the elderly with their canes, and parents with their toddlers in strollers. Shoulder to shoulder with millions of Hong Kong residents, we shouted: “Reclaim Hong Kong; Revolution of Our Times!”—a common slogan that appeared everywhere in 2019. It reflected Hong Kongers’ desire to shelve the extradition bill—proposed by Carrie Lam, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong. Lam used a murder case involving Hong Kong citizens in Taiwan as a pretext to propose extradition agreements with Taiwan, Macau, and China. Lam said the bill would prevent lawbreakers from committing crimes in one region and fleeing to another. The reality was that the bill would let the Beijing government arrest people the CPC deemed unsavory—activists, journalists, and even business executives, and subject them to its justice system with a 99 percent conviction rate. Naturally, Hong Kongers didn’t want this extradition bill—they feared getting caught up in the unjust Chinese legal system and rotting in a Mainland prison.

That summer, I observed the gathering each weekend and watched the number of protestors swell. In June, one million people were on the streets. By the first weekend of July, two million people marched and chanted through the major roads of Wan Chai. The government, however, ignored people’s demands and cracked down on peaceful protests. Soon, there were allegations that police officers beat commuters on the MTR, Hong Kong’s subway system, and some had died at Prince Edward Station, a station I passed through every day to and from work. No one knew what happened—according to the news media, the security footage disappeared, and there were speculations that the government destroyed evidence to conceal their atrocities. As a result, many young people in Hong Kong felt pacifism was futile and resorted to violence. Believing that the MTR was colluding with the police to harm them, they trashed subway stations. Furthermore, they also vandalized businesses—belonging to those aggravated by the protests that disrupted their livelihood—and branded them pro-Beijing. The police ramped up their presence around the city to maintain order and protect property. As Derek and I walked home with our groceries one day, we bumped heads with a group of militarized police. We dropped our shopping bags and raised our arms as they sped past us, chasing black-clad protestors.

Bearing witness to the atrocities in Hong Kong, I couldn’t help but think about my ancestral homeland of Taiwan, which made me root for Hong Kong even more. However, after six months of constant turmoil, the political situation drained and depressed me. Despite myself, I was also resentful: I had already fled political unrest in Bahrain ten years ago—how did I get thrust into another? Friends called me after hearing about the situation in Hong Kong. “It seems like revolutions follow you wherever you go!” they teased.

I chuckled along, but the city’s ordeal was no laughing matter. People were hurt; lives were upended. Life in Hong Kong would never be the same again.

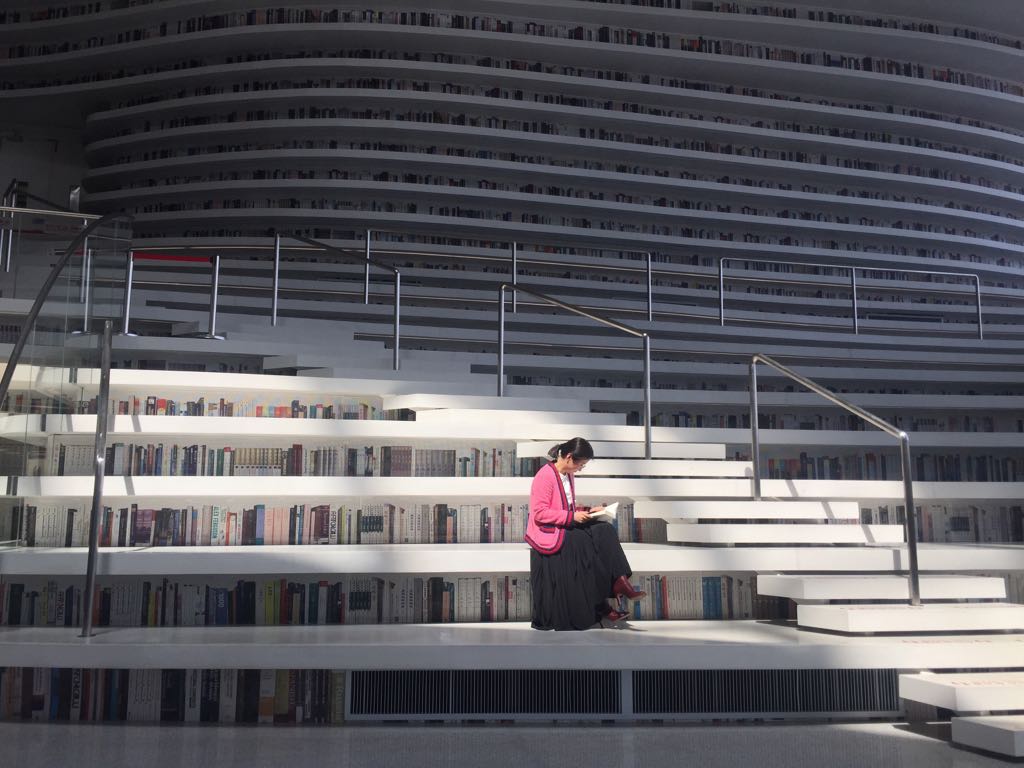

In 2012, I moved to Hong Kong not knowing a soul. I had just separated from my first husband and escaped the Arab Spring and Bahrain’s sectarian conflict—where burning tires blocked highways, and the smell of tear gas lingered in my neighbourhood—and landed in a maze of disorientating skyscrapers in the metropolis of “Fragrant Harbour.” Worn down by my failed marriage and driven by my desire to gain more professional experience, I moved to Hong Kong for a librarian position at a local university.

At this time, I was more concerned about establishing myself and finding love in my new city than worrying about the CPC’s growing power. So, I immersed myself in online dating. Many potential matches were excited that I lived in Wan Chai, famous for bars lit by neon lights that promised dancing girls and two-for-one drinks. “Shall we meet in your ‘hood for happy hour drinks?” They texted with the winking emoji.

I soon learned to steer clear of men who spent their weekends getting drunk in the red-light district of Wan Chai. On its main drag of Lockhart Road, the domineering, grandmother-aged madams congregated in front of bars shrouded by black draperies, tugging at men’s sleeves as they staggered by. When someone paused, smiled, or showed interest, a troop of young Southeast Asian women in cakey make-up and miniskirts swooped in and led him into their curtained establishments for a good time.

Back then, as a young Taiwanese Canadian expat in Hong Kong, the only thing that made me think about the other side of the border was who could be there. One day, I went to Shenzhen to meet a man I matched online. I gripped my Canadian passport with my single-entry visa at the Hong Kong-Shenzhen border. I was worried that a customs agent would see my face and demand that I produce some other kind of identification that showed that I was “Chinese.” Since my place of birth was Japan, I could pass for a non-Chinese person, but my Taiwanese surname might have given me away. I was wracking my brain with scenarios where I got into trouble as a foreigner imposter, but to my relief, the agent barely looked at me as I crossed the border.

My date met me at the train station. He was an American English teacher working on his first novel and not nearly as cute or cool as his profile suggested. However, since I had paid for the visa and gone through the two-hour ordeal of coming to Shenzhen, I let him play tour guide for the day. We walked through a shopping district and visited some tourist sights, but I couldn’t recall anything noteworthy—except that we walked by a Walmart. While having a mediocre meal, I complained about the lack of decent cocktails. After spending a day in Shenzhen, I deemed it unruly and unsophisticated, a stick in the mud in the backwaters of China.

By early 2014, I was bored with my job and the glitzy city that offered endless shopping expeditions and boozy weekend brunches. I was also frustrated by my lack of romantic prospects and the city’s noncommittal Romeos—the bankers, teachers, or journalists who wanted to get drunk and hook up. I didn’t feel connected to Hong Kong and found nothing and no one to keep me there. Therefore, I plotted my escape—instead of finding a professional librarian position in Canada when I finished my contract, I would move to the Philippines and become a dive instructor.

My plans fizzled when Derek entered my life. He was a typeface designer, a professor, and a “gentleman redneck” who hailed from the Indiana side of the Ohio River. He didn’t just want to get drunk and hook up. Instead, we went to a David Sedaris performance and a music festival. After that, we spent almost every waking moment together and texted each other nonstop when we were apart. Then, two weeks after we officially started dating, he told me he loved me and asked me what kind of engagement ring I wanted. Within four weeks, we flew to Taipei so he could ask my father for my hand in marriage. Ten months later, we were wed in Hong Kong, surrounded by family and friends.

After Derek and I married, he moved into my apartment in Wan Chai. We decided to make the Fragrant Harbour our permanent home, and I grew to love my neighborhood, which was more than a depraved watering hole. It existed at the intersection of contradictions—the seedy bars near a high-end shopping centre and a historic temple sandwiched between skyscrapers on Queen’s Road East, a major thoroughfare built on reclaimed land where the harbor used to open up to the South China Sea. On my way home from work, I stopped by my favorite stall in the Wan Chia market to buy Korean-imported socks in the narrow streets filled with kiosks selling tchotchkes, from the tacky “beckoning cat” lucky charms to counterfeit Calvin Klein underwear. I shopped for fresh vegetables and freshly butchered chicken on the weekends while hopping over puddles in front of live seafood tanks and snake soup stalls. In the bustling centre of Wan Chai was a ballpark with bleacher seating that separated the seedy part of the district from the rest, where people of all ages gathered to play sports and have picnics.

Hong Kong seemed to fall under Chinese rule overnight—I barely had time to catch my breath. Less than a year before the 2019 protests, the new high-speed rail service commenced between Hong Kong and Shenzhen. At that time, my wariness of the CPC had faded enough that I was tempted to visit when my friends boasted about inexpensive massages and spa treatments on the other side of the border. The pampering appealed to me, so I convinced Derek to join me for a leisurely weekend in Shenzhen.

Months before the trip, my mother convinced me it would be more economical and convenient to enter China with the “Taiwanese Compatriot Permit.” It is a travel document for Taiwanese citizens to enter China since the Chinese authorities don’t recognize the Taiwanese passport as a legitimate travel document. I agreed to let my mother apply because I otherwise would have had to pay for a non-transferable ten-year tourist visa on my Canadian passport, which was expiring in less than two years.

On a Saturday morning in late September 2018, Derek and I arrived at the newly built Hong Kong West Kowloon train station. We went through security and stopped at a well-stocked duty-free shop. Recalling my annoyance about the lack of quality alcohol in Shenzhen six years ago, I picked up a bottle of Roku, a Japanese gin, before going toward the passport control area. A thick black line with a thinner yellow line was in the middle outside the duty-free shop. In both Chinese and English, it said, on one side, “Hong Kong Port Area,” and on the other, “Mainland Port Area.” Once we crossed the threshold, all the signs changed from traditional to simplified Chinese. This jarring shift in the writing system indicated that I was entering the realm of the authoritarian CPC.

The passport control area has two sections: “Chinese Nationals” and “Foreigners.” Derek made his way to the

“Foreigner” section. In the past, I entered China as a Canadian, a foreigner. But this time, by showing up with my “Compatriot Permit,” I was no longer Canadian—as far as the border customs agent was concerned, I was Chinese.

I sighed. “Hey, sweetie,” I said, turning to Derek. “I think I should probably go to the other line.”

We kissed each other goodbye, and I made my way to the other side, hating every minute. In my head, I was screaming: “I’M NOT CHINESE! I’M TAIWANESE!” But, I barely felt Taiwanese—I wasn’t even born there and had only lived there for four years as a child. Even though I grew up in Canada and spent most of my adult life in the Middle East and Hong Kong, in the eye of Chinese border control, I looked the part, and with my travel document, I was definitely a “Chinese National.” At this moment, I wondered if the money I had saved and the convenience my mother had touted were worth this identity crisis.

The line moved faster than I expected. Within ten minutes, I was through. After my weekend bag went through another security check, I was surrounded by thousands of people in the terminal. Derek was nowhere to be seen.

Where are you? I texted.

Still in line. Derek texted back. It barely moved since you left.

I found our gate and texted Derek again. Hey, the train is going to leave in twenty minutes. Are you almost through?

I hope so. He texted.

I groaned. I distracted myself with Instagram, calming my nerves with luncheon spreads, beach vacations, and cat portraits.

Then, five minutes before the train was supposed to depart, I called Derek, “The train is leaving soon. Are you going to make it?”

“I am running toward you,” he yelled into the phone. Then, I spotted him scrambling to gather his bag at the security checkpoint and making a beeline toward me. Together, we sprinted to our gate. We made it on the train seconds before the doors closed.

Once we got off the train, we found ourselves in a spacious, spotless train station and followed the sign to an orderly taxi stand. In the cab, I told the driver the name of our hotel in Mandarin. Unlike some taxis in Hong Kong, this one was clean, free of stale cigarette smoke stench. The driver was courteous, and his driving etiquette was impeccable, unlike the cabbies in Hong Kong who crisscrossed the city in jerky, vomit-inducing brakes and cussed loudly when stuck in traffic. To my delight, I felt a breeze on my face—in Hong Kong, if the cab window were open even a crack, we would have been suffocated by exhaust fumes or deafened by the incessant honking. However, public vehicles and taxis in Shenzhen were electric, making the air cleaner. On the fourteen-lane highway, there was enough room for everyone, reducing the need for honking. There were even bike lanes.

We explored Shenzhen via the MRT, the public railway system. First, we had a relaxing massage and ate delicious and cheap spicy mudbugs—Derek’s favorite. Then, we went to the Overseas Chinese Town at night, famous for hip bars and restaurants, not unlike those in Wan Chai. We saw paintbrushes in a jar poking out of a window as we walked around.

“Look, they have studios here,” Derek said, pointing toward an old industrial building. “I bet you can rent a space here cheap.”

“Wouldn’t it be amazing to have a studio?” I sighed as my head filled with visions of life economically unattainable in Hong Kong.

On our final morning, we visited the Dafen Oil Painting Village, famous for oil paintings dedicated to the reproductions of masterworks, from Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Van Gogh’s Starry Nights to Monet’s Lily Pond. This village supplied the world’s doctor’s offices and gift shops with the most realistic-looking fakes.

In a taxi to Dafen, we drove by massive housing complexes still under construction.

“I wonder how big those flats are.” Derek mused, “I bet we could get more space for our buck out here.”

Shenzhen seduced me. Not knowing what would happen to Hong Kong within the year, modern China almost convinced me that it was more advanced than Hong Kong, with abundant housing, electric cars, and bike lanes.

When we arrived in Dafen, it was drizzling. Easels were set up before every storefront, where artists demonstrated their painting techniques, copying the masterpieces from photographs. Even up close, the fakes were impressive—serious training went into creating them. But after we got over the initial marvel, we realized that the whole village was the same thing on repeat. I was wet and bored and demanded we leave.

“But isn’t it ironic that while China is trying to demonstrate progress and innovation, it has a whole village dedicated to copying masterpieces from the West?” Derek chuckled as we stepped out of Dafen.

We stood by the main road but couldn’t find a taxi. So, we searched for a subway station. This was an older part of town, rowdier and dirtier. The electric vehicles were gone; the clogged roads were filled with exhaust-spewing cars—this was China that matched the image in my mind. Then, we stumbled upon a Walmart. It wasn’t the same one I saw on my first trip to Shenzhen, but I convinced Derek to go in with me. Unlike the North American megastores, this one had no spacious aisles and logical signages. Instead, salespeople hollered at the top of their lungs, and shoppers elbowed each other through the crowded space. The scent of death clung to the air as we walked near butcher stalls.

“Ugh, even the Walmart is a rip-off,” I moaned.

Derek pointed to something behind me on the jam-packed train on our way back to the hotel. Our train accelerated through a three-block-wide housing estate. They were about fifteen stories each and no older than thirty years. Some buildings remained intact among the imposing cranes and menacing bulldozers, while others were half torn down. Most of their windows had been knocked out, revealing dark, empty interiors, and the cityscape of Shenzhen poked out of the jagged concrete structures. The view was fleeting but made an impression—it was the first of many we witnessed—remnants of homes torn down to pave the way for the newer, shinier Shenzhen.

Spending a weekend in Shenzhen gave me a glimpse into Hong Kong’s future. I couldn’t help but wonder: In the eyes of new China, how much of old Hong Kong would survive? Reflecting on the smog-free fourteen-lane highway, the trendy artist district alongside the copycat painting village, and the half-torn-down housing estates, I was disheartened to imagine Hong Kong’s future devoid of its contradictory charms: The upscale French restaurant in the puddle-filled street market, the prurient, neon-lit Lockhart Road next to a basketball court where children play, and the tiny temple dwarfed by glass skyscrapers. I love Hong Kong because it was a haven where quirks and weirdness were allowed to exist, a city that had room for resistance and diversity instead of snuffing them out.

§

Derek and I left Hong Kong in December 2019 after witnessing months of crackdowns. Militarized police patrolled Wan Chai daily. Public transportation and businesses halted operations anticipating new clashes between the protestors and the police. Like in Bahrain, I was again subjected to unpredictable road closures and tear gas thrown around my neighborhood. International companies shuttered their Hong Kong offices, and our friends left in droves. As a Taiwanese woman, I felt unsafe in Hong Kong, even with my Canadian citizenship. When Derek got a job in Sri Lanka as a dean at a design university, we packed up our Wan Chai apartment and bid our Fragrant Harbour goodbye.

Two years later, after shuffling around Sri Lanka and the US during a global pandemic, Derek and I made Taiwan our home, despite its volatile relationship with China. Friends and family worried about our safety, but we reminded them that Hong Kong and Taiwan differed. The former was always going to be reunified with China according to the Sino-British Joint Declaration—but instead of maintaining Hong Kong’s capitalistic status quo until 2047, the CPC took control of the territory twenty-seven years ahead of schedule. With the implementation of the National Security Law in 2020, freedom of speech in the former British colony vanished overnight. The government banned the annual June Fourth Vigil. The popular slogan, “Reclaim Hong Kong; Revolution of Our Times!” became illegal, and anyone uttering it or displaying it was arrested. The border between Hong Kong and Shenzhen will soon be a thing of the past—old Hong Kong will be integrated into new China—the carefree, freewheeling city-state will solely exist in the collective memory of those who called it home.

On the other hand, in Beijing’s eyes, Taiwan became a renegade province when the rebel Kuomintang fled to the island in 1949. Chiang Kai-shek established his government in Taiwan and always planned to retake mainland China. He never succeeded. During his reign, he imposed martial law to squash dissidents and created an environment of terror until his death. In 1987, his son Chiang Ching-guo lifted martial law, and Taiwan had its first election in 1996. Slowly but surely, Taiwan shed its brutal authoritarian past and emerged as a beacon of democracy.

For the last decade, my feelings about CPC have oscillated from indifference and apprehension to panic—with a brief and misguided moment of enamor. As CPC under Xi’s rule becomes more powerful, Taiwan’s future is uncertain. Beijing’s track records in Hong Kong and Xinjiang are not reassuring, and I worry about what will happen to Taiwan if the CPC takes it by force. Yet, Derek and I love this island my Chinese ancestors made home over three hundred years ago—with its modern convenience, superb healthcare, and proximity to the rest of Asia, we can’t imagine living elsewhere. Therefore, I have to learn to channel the carefree attitude of my fellow Taiwanese—eat braised pork over rice at my local diner, enjoy a weekend island holiday, and live one day at a time.