For the longest time, I considered myself a multi-generational Taiwanese person. We have a six-meter granite plaque in the Chang family cemetery that outlines how my ancestors left Fujian and crossed the strait in 1742, making me the twenty-second generation in Taiwan. My mother’s family, the Lins, have also been in Taiwan for hundreds of years. However, I learned recently that not all sides of my family have been in Taiwan for hundreds of years.

Since moving back to Taiwan in 2021, I’ve lived in my paternal grandmother’s house. She’s ninety-four years old and her house is in desperate need of repairs. While my husband Derek does the majority of the renovation, I’ve been organizing and maintaining her personal belongings and documents.

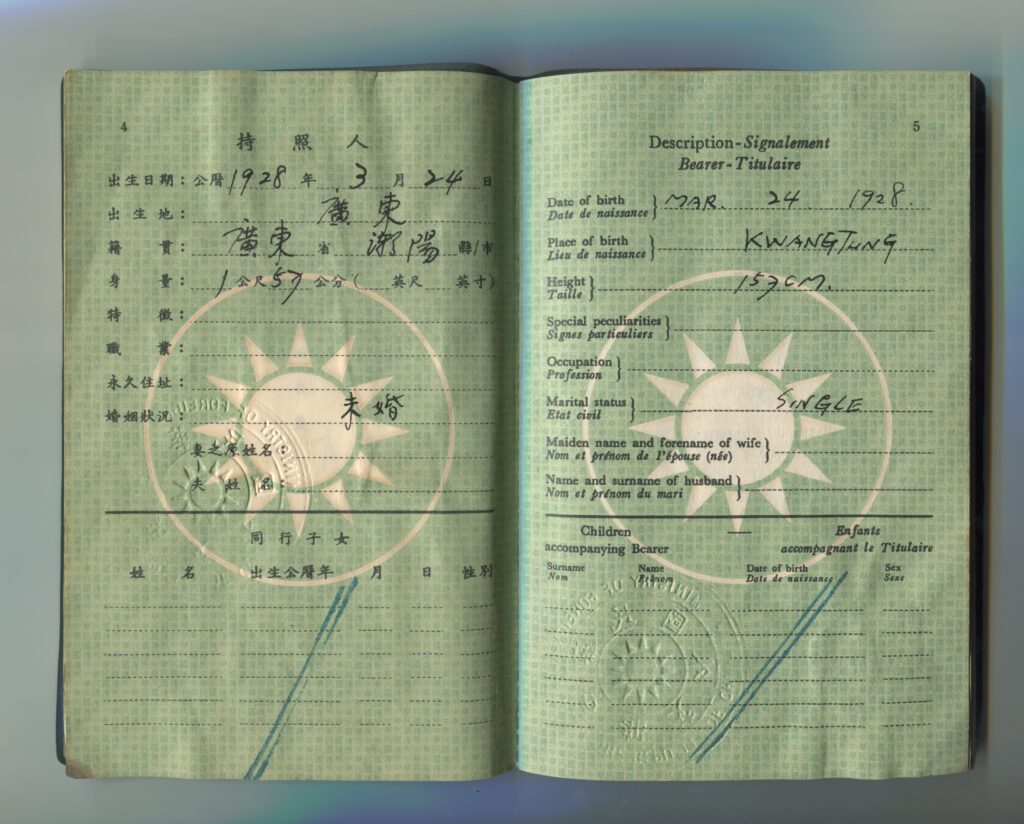

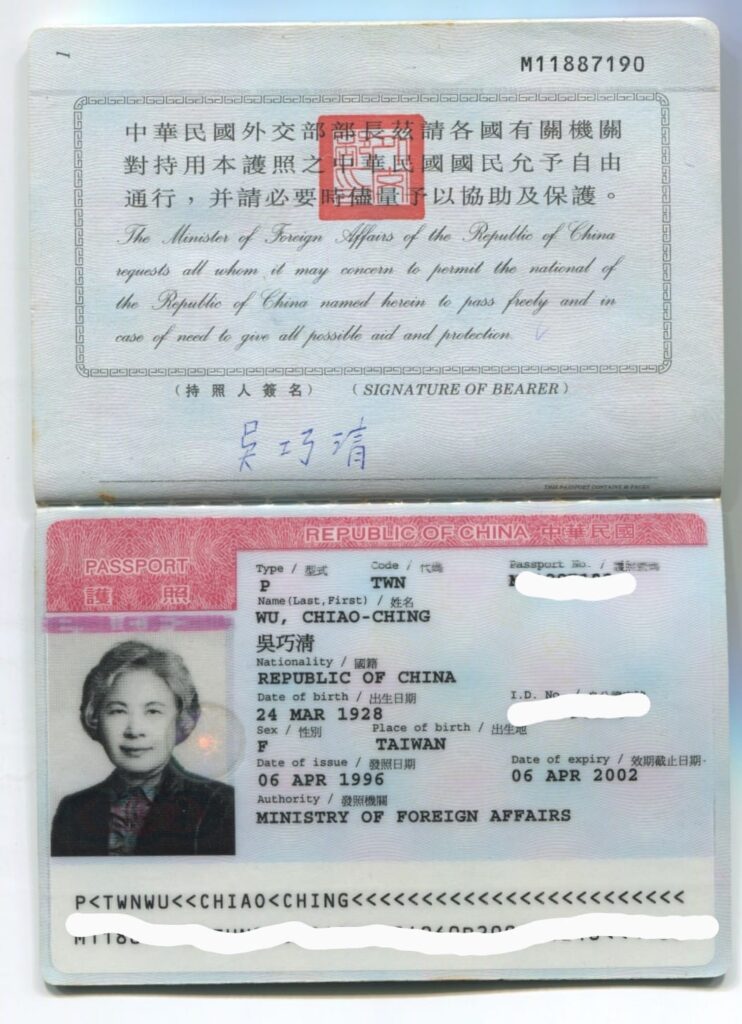

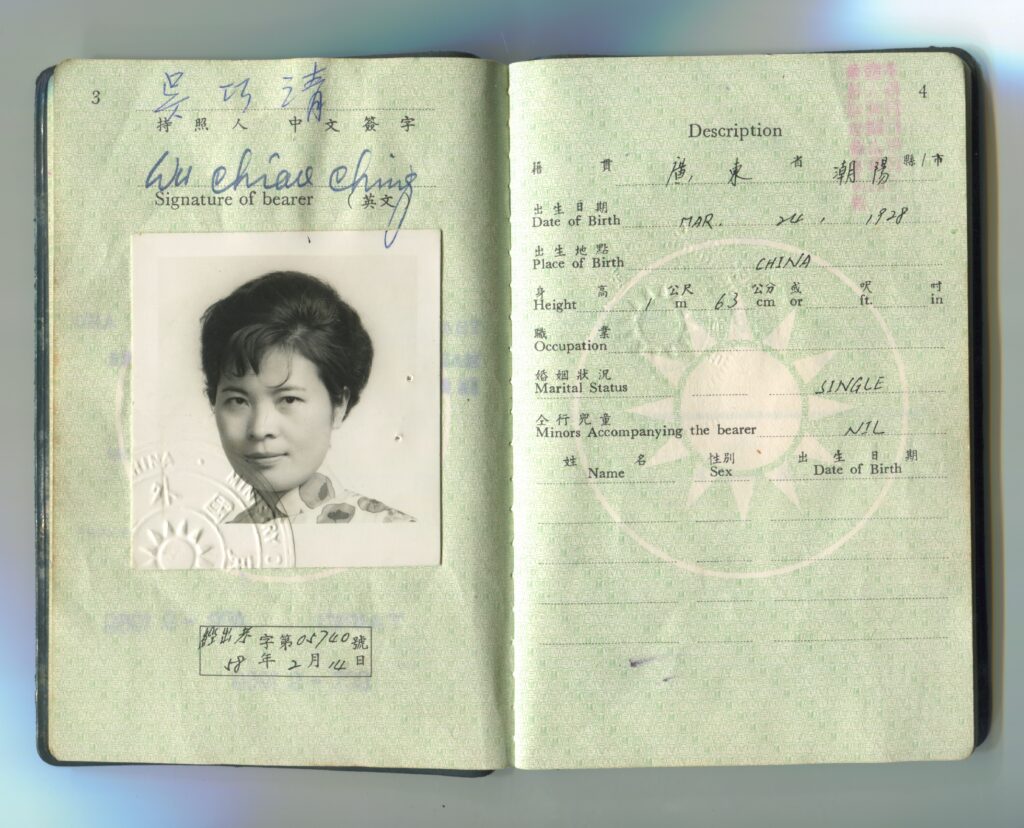

Ama’s documents are fascinating. They consist of photographs and various types of documents, which gave me clues to her early years. Ama’s passport from 1965 claimed that she was born in “Kwangtung” (廣東—more commonly spelled “Guangdong” ). Yet, her passport from 1996 claimed that she was born in Taiwan. When I asked my father, he was confident that Ama was born in Taiwan. Back then, people listed their “ancestral home” (籍貫) on their identification documents, but it wasn’t necessarily where they were born. Also, during Kuomintang (KMT) rule, Chiang Kai-shek believed that his government was China’s legitimate government, and therefore, it’s not unreasonable to list someone’s birthplace as “China.” So, with all this conflicting information, where was my paternal grandmother born?

To learn more about Ama, I decided to dig deeper by looking into her father, Wu Fu-ke. My Granduncle, born to my Great Grandfather’s second wife, said his father was born in Guangdong province and came to Taiwan when he was about thirteen. He eventually married my Great Grandmother, who was Taiwanese. They had two sons and seven daughters. When Great Grandfather was about fifty years old, he moved his wife and some of his children to Vietnam. Granduncle gave me approximate years, which prompted me to the household registration office to locate the earliest records on my Great Grandfather to establish his timeline.

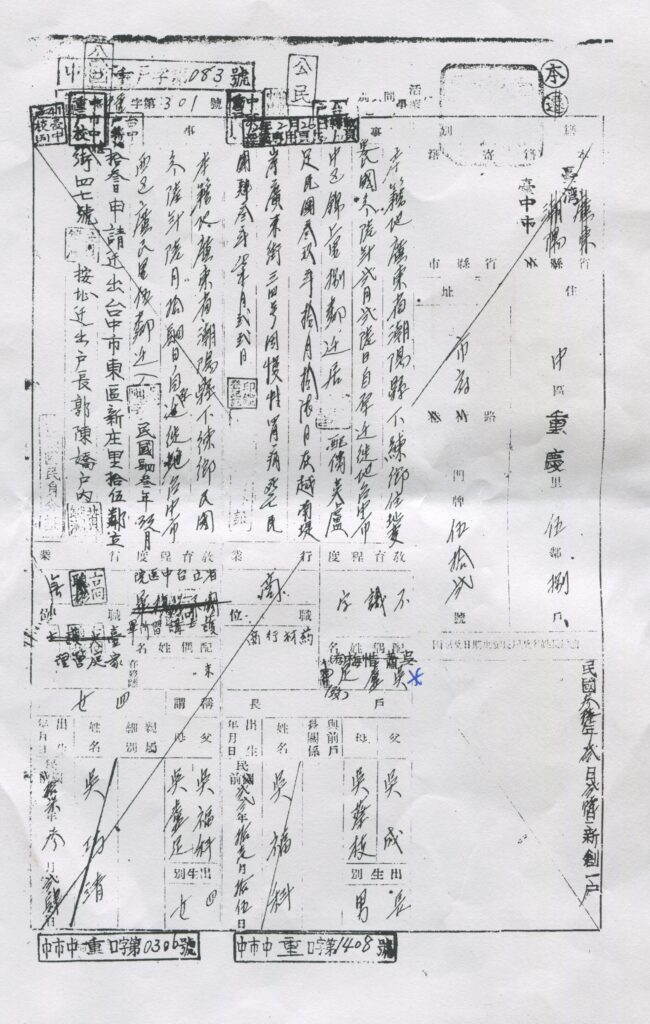

The clerk at the office handed me two documents: one from 1914 and another from 1947. The 1914 form indicated Wu Fu-ke, approximately twenty-four at the time, was registered with a different family (due to privacy laws, the record doesn’t show who he was staying with). The document from 1947 showed that his wife (my Great Grandmother) had died in Vietnam in 1950. Furthermore, Ama also deregistered herself from her adoptive mother‘s house and into her father’s house in 1947. She would have been nineteen at the time.

The household registration forms muddled my investigation because they didn’t match what I thought I knew about Ama or her family. What’s crazy is that my Great Grandfather’s birthdates weren’t the same in the two documents. One claimed that he was born twenty-two years before the Republic of China (ROC); the other claimed that he was born twenty-three years before the ROC. This would put my Great Grandfather’s birth year to 1889 or 1890.

I also asked for Ama’s earliest records at the Household registration office. According to the clerk, the earliest one was from 1947, when Ama was nineteen. That was roughly the time her father moved back to Taiwan from Vietnam. I was hoping to find out when she was registered at her adoptive mother’s house to ascertain when her family left for Vietnam, but I haven’t yet to find this record.

Physical records, especially ones from previous generations, are unreliable—the Household Registration clerk told me that records were created based on what people had reported. And until the last half century, most people gave birth at home, and it wasn’t common to register one’s child immediately. My mother, born in 1954, wasn’t registered until she was three months old because her family wasn’t sure if she would survive. As a result, the birthdate on her official identification differs from her actual birthdate.

I may never know for sure if Ama was born in Taiwan or when she was adopted. However, based on photographs and what Granduncle told me, perhaps Ama was given away even before her birth family moved away to Vietnam—I may never know for certain. It’s unlikely that I could define the exact timeline of Ama and her family through official records. There’s a part of me that wants to solve this puzzle, but I may never know the specifics of Ama’s early years or the dates of my Great Grandfather’s migration—from China to Taiwan, then from Taiwan to Vietnam, and back to Taiwan again. I could only go by what my father, my Greatuncle, and Grandaunt, told me—the family members who have known Ama and my Great Grandfather—and create a narrative based on their reliable memories. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter when my Great Grandfather came to Taiwan or where Ama was born. It doesn’t take away who I am as a Taiwanese Canadian woman on a journey to learn more about her family and history.

Even though my project is about my family, it is also about Taiwan, its history and politics. The idea of “Taiwanese-ness” is nuanced, and even my idea about Taiwanese identity has evolved over the years. I used to identify as Chinese ethnically but culturally and politically Taiwanese. Now, I strictly identify as Taiwanese, and yet, ironically, I found out that my Great Grandfather was born in China, and my paternal grandmother may have been born there too. However, my discovery hasn’t challenged my Taiwanese identity, but it only deepens my conviction that Taiwan and China have an intimate and intertwined history.

I love Chinese culture and China as a place—after all, my ancestors came from there. Due to escalating tensions, we often forget that Taiwan and China share so much commonality, from languages to food to customs. I’m not opposed to China, but what I reject is the Communist Party of China (CPC). I denounce the CPC’s authoritarian politics to snuff out diversity in religion, ethnicities, and languages. I condemn the Beijing government’s treatment of the ethnic Uyghurs in Xinjiang and the violent suppression of Hong Kong’s democracy movement in 2019. In China, to be patriotic is to love one’s country and its government. For many of us in Taiwan, there is a clear distinction—we could love our country but also criticize our government. We could vote and choose who governs us. However, China has not reached that point yet. There is no separation between the country and the party. Maybe one day, when they can separate the two, there will be a new China, perhaps one that Taiwan wouldn’t mind joining. Despite Xi’s one China rhetoric, I’m a firm believer that the fate of Taiwan should be decided by the Taiwanese people.

Thank you for sharing this. I am multi-generational Taiwanese on both sides of my family, and my grandparents only spoke Taiwanese and Japanese. my mother was born in the Japanese sector of Shanghai, because her family lived there for 4 years, but my family is very strongly Taiwanese in its identity. Her only memory of Shanghai is of KMT soldiers taking over her family’s home after Japan declared defeat in WWII…

It’s enlightening for me to read that you identify as Taiwanese, even if your roots in China are stronger than mine. My parents gave me the impression that this was not the case for ‘waishenren’.

It is a shame that the CPC has tainted the world’s view of what it means to be Chinese, and what China is… I hope as well that the Taiwanese people will be able to determine their own fate too.

Im so happy that i found your post coz we are the the same with our grandparents but mine actually my grandfather and base on his place of birth is from (kwantung)also same as yours but he died early so i only have 1 passport of him but i wondered and maybe you are right that there descendant lives they put kwantung but when i ask my mom she also said that my grandfather always told them he was born in formosa so meaning he also born in taiwan also…but i want to know if your grandparent passport of 1965 if she have a id.no.pr personal id.numner on it?like her 1996

Im so happy that i found your post coz we are the the same with our grandparents but mine actually my grandfather and base on his place of birth is from (kwantung)also same as yours but he died early so i only have 1 passport of him but i wondered and maybe you are right that there descendant lives they put kwantung but when i ask my mom she also said that my grandfather always told them he was born in formosa so meaning he also born in taiwan also…but i want to know if your grandparent passport of 1965 if she have an id.no.printed or handwritten on it?like the 1996 passport that have I.D.number printed?