Growing up is hard. Growing up when your parents are thousands of miles away is even harder. Lucky for me, I had a champion. His name is Dr. Roman Onufrijchuk.

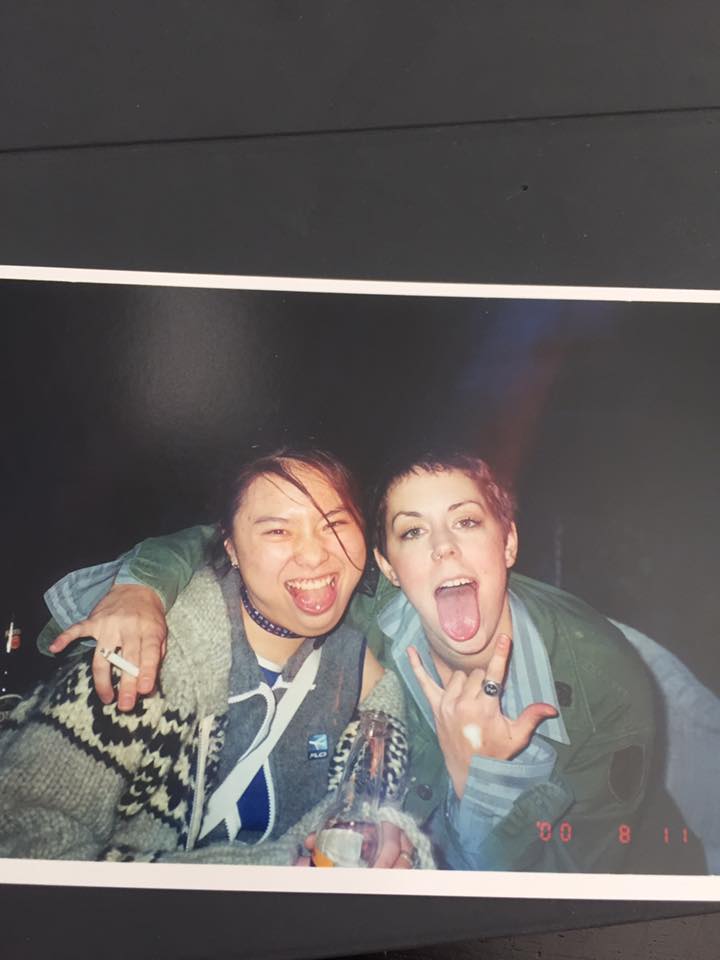

I met Roman in the spring of 2001. He was my professor in a class called “Sociology of Leisure.” We became close when I told him that I couldn’t do my presentation in class because I was hungover from doing cocaine the night before and hadn’t done my reading. Since that class, I followed him around like a shadow.

At any given time, Roman was parked at a table on the spacious and shaded patio of Tree’s Café on Granville Street in the business district of downtown Vancouver, a mere two blocks away from campus. In front of him on the table was a worn black plastic case filled with Gauloises cigarettes, an ashtray half full of orange filter tips with yellow flecks, a full cup of foamy café macchiato and an empty porcelain cup stained with coffee sediments.

Roman was a distinguished looking gentleman with a neatly trimmed grey beard. His usual attire is a black fisherman’s hat, a khaki button-up shirt, cargo shorts and sporty sandals. Though he looked like he might be going fishing, he was not the type to do so. His blue eyes were deep, indicating many lifetimes worth of stories. The way he sat in his chair slightly slouching with a cigarette between his nicotine-stained fingers, he looked wiser than his 51 years.

A current day Aristotle, Roman is a sage-like character who enjoyed retelling the Greek mythologies to any student who would listen. Like Aristotle’s Lyceum, Roman had his Tree’s Café where he counseled students, the members of his so-called “tribe.” Gregarious in nature, he was fond of adopting “strays,” those troubled students on whatever brinks they were on. He took these directionless souls under his wings and nurtured them with his infinite wisdom and generous attention. I was an active member of this tribe and saw him about everything, from research papers to unfortunate romantic encounters.

Roman put out his cigarette and waved me over as I approached the patio. He had a bad habit of smoking only two-thirds of his cigarettes. He wrapped up the conversation with the student in front of him. “Thank you so much, Roman.” The student said as he stood up to leave.

Roman lit another cigarette as I took the seat across from him. “You okay?” he asked in his gruff but modulated radio voice, one that had been soaking up tobacco and whiskey for years.

“Ugh.” I moaned as I dug through my massive, bottomless purse for a lighter. Roman leaned over the table and lit my cigarette. “Thanks.” I exhaled.

“That bad eh?” Roman chuckled, “So, what now?” Roman asked, his blue eyes twinkled with a hint of laughter.

I began to narrate the most recent episode of my boy drama. Roman smoked and listened patiently as I told my woeful tale.

When I finished, he took a puff from his cigarette, “Well my dear,” he exhaled, “You should never go to bed with someone who’s got more problems than you.”

“But how do I know he’s got more problems than me?” I whined.

“You learn, kiddo, by paying attention.” He winked and took another puff from his cigarette, “In the meantime, this guy sounds like a bozo. Lose him.”

His attention drifted to something behind me, “My next date is here.” He announced as he stubbed out his cigarette, “You’ll be okay. Don’t go around breaking too many hearts.”

“But I still need to talk to you about my paper!” I wailed in a panic.

“Fine, come back in about an hour.”

All day long, when Roman was not in class, he sat on this patio smoking his cigarettes, sipping on his café macchiato and advising students on all aspects of their lives.

Everybody needs a champion. With Roman’s guidance and constant encouragement, I eventually graduated with honors. I went to graduate school, and after graduation started my career as an academic librarian. In my career in Dubai, Bahrain and Hong Kong, I met plenty of students who needed that extra push and a pat on the back. Everywhere I worked, I tried to channel Roman— it’s only fair that I give back what was so generously given to me.

Roman was my teacher, my mentor, my friend. In June 2015, I was devastated to learn that Roman passed away. I never had a chance to say good-bye. I was heartbroken that Roman never met Derek, my now husband, after hearing so much about my boy drama over the years.

Derek held me tight. “I understand what Roman means to you.” He whispered, “And I get to meet him every day through you.”