Hello dear reader,

Today, I am sharing “The Nikah” which was originally published and featured in the March 2019 issue of Sunspot Literary Journal. I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Tears

rolled down my powdered face, dampening my makeshift lavender headscarf. I bit

my lower lip and cried without making a sound. I could have said no to Gökhan and

walked away from the nikah, the

Islamic wedding ceremony—but my conditioning would not allow it. Growing up in

a Taiwanese family, the concept of “losing face” was ingrained in me.

I understood how unforgivable it was to humiliate someone in public. I felt

compelled to submit to the conditioning that I have willfully fought against my

whole life, to maintain my future husband’s honor in front of his entire clan.

But the obligation to compromise my integrity, whether it was real or

imaginary, was crushing me. I hated having to pretend to believe in something

to please my future mother-in-law.

Gökhan’s

mother was a gregarious Turkish woman. Short and squat in stature, she was the

matriarch of the family. She had moved to Denmark with her husband in the ’70s,

and all her children had been born and raised there. However, she held onto the

customs from the old country and behaved very much like a traditional Turkish

wife and mother. I never saw her without her headscarf, even in the middle of

summer. Gökhan’s father, on the other hand, had adapted to Denmark. He was a

quiet man with a handsome, honest face. He owned a grocery store in the

neighborhood, and when he found out that I loved strawberries, he’d bring some

back from his store every day during my visit. He was the type who would go

with the flow and let his wife take care of all the traditions and rituals.

I

had just arrived in Denmark a week earlier and had met Gökhan’s family for the

first time. We slept in separate beds because his mother thought it was

improper for us sleep together until we perform the nikah.

That summer, Gökhan and I were in-between places—we had

just left Dubai and in the autumn moved to Bahrain where I would start a new

job. My new employers instructed me to move to Bahrain alone, or marry Gökhan

so I could sponsor his dependent visa. Since we did not want to break up, we decided

to elope in Canada. We made a pitstop in Copenhagen on our way to Vancouver to

see his parents before we legalized our union.

Even

though Gökhan’s mother and I did not speak the same language, I wanted her to

like me. I understood that the nikah

was pivotal to his pious mother. I was not against it, but I also did not want

to give her the impression that I was willing to convert to Islam. I am proudly

secular, which caused major friction when Gökhan and I first started dating.

“If

you want to be with me, and be accepted by my family, you will need to

convert,” he said—it was the only time I remember Gökhan being adamant about

anything.

“No.”

I stared at him as if he had warped into a goat. Converting to Islam was unthinkable. Being secular is my mode in

life, and I was not willing to change it.

He

explained that all I had to do was to pretend, to do it for a show, which was

what he had done his whole life. I still refused. He called me spoiled,

stubborn and selfish. I cried but persisted. It was a battle of wills that

lasted the whole day.

“If

you love me, you will accept me for who I am,” I argued, my eyes blazing. “You

wouldn’t ask me to compromise my integrity.”

Eventually,

I broke him down with a combination of persistence and tears. “You won’t need

to convert,” he said, hugging me. “I will talk to my mother.”

It

was no surprise that Gökhan yielded—I was the girl who always had her way.

“Don’t smoke in the mall,” Mama used to glare at me when I was on my way out of

the house when I was in high school, “someone might see you.”

You don’t want me smoking in the mall? I did just

that with abandon. Don’t want me dating white guys? I did, just to make you

cringe. Oh, you would disown me if I got a tattoo? I did, just to test you.

Gökhan

was right: I was spoiled. Mama relented, and Gökhan did too.

My

initial experience with Islam was when I moved to Dubai for my first job as a

librarian, about ten months before meeting Gökhan. My first impression was that

it was strict and conservative. I had to abandon wearing skirts to work because

it was indecent to show my knees. The religion forbade many things that I enjoyed,

such as alcohol and pork. During Ramadan, even non-Muslims could not have a sip

of water in public. However, I kept an open mind. I wanted to be involved with

my future husband’s traditions.

When

Gökhan told me about nikah, I knew

nothing about it. He described it as an engagement to tell Allah that he, Gökhan,

had chosen me, Kayo, to be his wife. That did not sound awful—it seemed like a

symbolic ceremony. I agreed that I was willing to take part in the nikah, as long as I did not have to

convert to Islam. He talked to his mother who agreed that I would not have to.

Overjoyed that her son would no longer live in sin, she invited the whole

extended family, prepared an elaborate spread, and summoned the prestigious imam, a religious leader, who would

officiate the ceremony.

I

had no idea what I signed up for.

On the day of the nikah, I was in the center of the room wearing an ivory,

ankle-length, cotton maxi dress with grey embroidered flowers at the hem. I’d

bought the dress a few days before because it was long and covered my legs. However,

the top portion was too revealing for Islamic taste, so I wore a grey cardigan,

buttoned-up all the way, which hid my tattooed arm and immodest cleavage.

Gökhan’s

three aunts were fussing around me, trying to pin a lavender pashmina over my

head as a temporary headscarf. His little sisters, aged 11 and 13, whose room

had turned into a bridal dressing room, stole curious glances at me. When I

returned their stares with grins, they gasped, turned their heads and looked

away. His boisterous aunts laughed and chatted in a combination of Turkish and

Danish. They clamored and made animated gestures with their hands and clapped

as they giggled over some anecdote I couldn’t understand. I stood amid this

commotion with a dumb smile on my face and nodded my head as Gökhan’s only

English-speaking aunt asked me if I was doing okay. Despite the chaos in the

room, a part of me was having fun, soaking up his aunts’ contagious excitement.

I felt euphoric and found myself smiling more as time passed. I was putting the

finishing touches on my makeup when Gökhan poked his head in the room, “Hey,

can I talk to you for a minute in the next room?” he asked in a quiet voice,

avoiding my eyes, his thick, dark brows furrowed.

“Is

something wrong?” I asked.

***

How

did I, my mother’s rebellious and stubborn daughter, ended up participating in nikah with a Danish-Turkish guy she had

only dated for less than a year? The truth was that the defiant teenager who

continually stretched boundaries and pushed her mother’s buttons found herself

a lost and scared 26-year-old woman in the Middle East.

I

was born in Japan to Taiwanese parents and grew up just outside of Vancouver,

British Columbia. I always prided myself on being an adaptable third-culture

kid—I was fearless and foolish. Fresh out of graduate school, I moved to Dubai

to start my first job as a librarian, even though I would not have been able to

find the city on an atlas.

When

I first got on the transport bus to the terminal of the Dubai International

Airport, I burst into tears—the warm and humid air tinged with dust reminded me

how far away I was from home. Homesickness was only one of the many challenges

I faced in Dubai. For the first month, I tried to get an internet connection in

my apartment to stay in touch with my faraway family and friends. I spent all

my free time going to Etisalat, the national internet provider. Each time, I

spoke to an indifferent woman at the counter who wore a black headscarf and

emitted an intense frankincense perfume. Each time, she told me, “two weeks, in’shallah.” Each time, I left the

building defeated and depressed. Before I knew any better, I was convinced that

‘in’shallah’ meant ‘go away.’ It took

over two months for me to have an internet connection at home.

On

the weekends, I would roam around the city wide-eyed, trying to absorb this

strange, desert landscape filled with glitzy shopping malls and imposing

skyscrapers surrounded by endless construction sites. As I walked by in my

short-sleeve t-shirt and knee-length skirt, South Asian workers gawked at me

with their unblinking, saucer eyes. I ran away to divert their gaze. I was

confused, misunderstood, and isolated from everything and everyone I knew.

Within

days of arriving in Dubai, I cried on the phone to Mama. After three days of

crying, Mama broke down and came for a visit. She cooked for me, helped me

settle into my new apartment, and we explored the city together. We shopped in

the souk, went dune bashing in the desert, and had afternoon tea at the Burj Al

Arab. However, after she left, I was even more homesick and lonely, which drove

me to go out to meet new people. Eventually, I made friends with other expatriates,

young women close to my age who had also moved to Dubai for their careers. But

they did not ease my sense of alone-ness. What I wanted was someone to come home

to and wake up next to every morning. Someone who would understand me, someone

to go on adventures with, someone who would take me away from this loneliness

and despair. After dating Gökhan for a few months, I thought he could be that

person.

The

truth is, my definition of a good relationship was simplistic and naive. I did

not know a thing about a healthy relationship—as a teenager, I watched my parents

struggle with their marriage. At the tender age of fifteen, I found out that

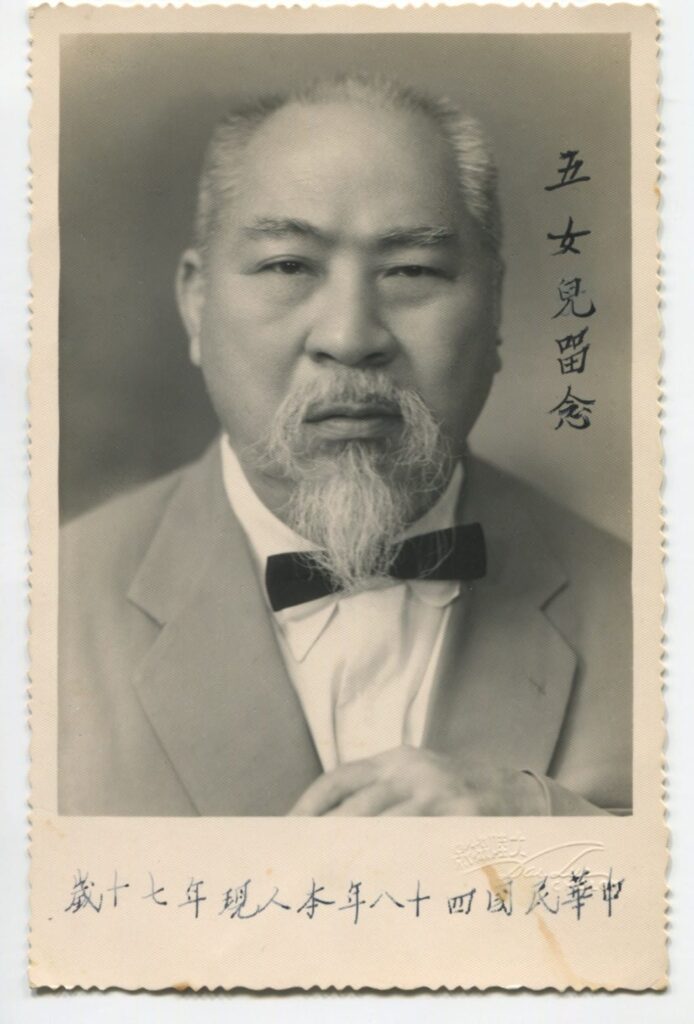

Baba, my father, had been cheating on Mama.

Baba

was a travel guide and was often away from home. At this time, Mama was in her

mid-30’s, but she dressed and acted like a much older woman— a dedicated mother

whose husband was away for long periods. Since Mama spent her days cleaning and

cooking, she paid little attention to her appearance. Her clothing of choice

consisted of dowdy, faded sweatsuits. Her world revolved around Baba, my

younger brother Davis, and me.

Before school one morning, I was eating my

eggs sitting on the high stool next to the kitchen counter when I heard Mama

scream Baba’s name. I am not sure what business Mama had poking around Baba’s black

nylon side bag— maybe she was putting something in there, or perhaps she was

looking for something for him— either way, she pulled out a love letter in

Baba’s handwriting, addressed to another woman.

Mama lost her mind with this discovery. She

wanted answers. She needed reassurance. She demanded Baba to explain himself. He

could not. He ran out of the door with his luggage to catch a flight and left

behind Mama who had turned into a wailing mess. I do not remember how I got to

school that day.

After

school, I found Mama standing disheveled in the middle of the kitchen, wearing

her frumpy, pale pink cotton nightgown even though it was three o’clock in the

afternoon. With tears streaming down her face, she wailed and screamed that she

wanted to die. She clutched a crumpled-up letter in one hand and with her other

hand, made slashing gestures with a kitchen knife as if she was going to slit

her wrist. I was terrified.

Several

days later, I came home, and the house was silent. Before this whole fiasco,

Mama always had a snack ready by the time I came back from school, like a

brothy bowl of Taiwanese-style beef brisket noodle soup, savory braised pork

with rice, or flavorful soy-sauce marinated chicken wings. But that day, when I

wandered into the kitchen, she wasn’t there. She was not at her usual station

in front of the stove, engulfed in tantalizing steam coming out of a bubbling

pot that she was stirring, telling me that my snack would be ready soon.

The

eerie stillness was a stark contrast to what had happened in the kitchen only a

few days before. I began to search the house to make sure Mama had not hurt

herself. At the entrance to my parents’ room, I held my breath, turned the

doorknob, pushed open the door and tip-toed inside. I entered the room inundated

with the stale, feminine odor of unwashed hair—the scent of desperate sadness. Mama

was asleep and snoring loudly even though it was the middle of the afternoon.

Her jet-black hair matted on the cream-colored pillowcase. Her usually smooth

forehead crinkled with despair—even in her sleep, she was in agony. On the

nightstand, I saw bottles of pills. Sleeping pills, seductive, secret sleeping

pills that promised peace and a pain-free slumber. I picked up a bottle and

rattled it—it was almost empty. I gathered every bottle in sight and took them.

I rushed into my bedroom and threw them in the bottom drawer of my nightstand

where I had stashed all the knives in the house a few days earlier.

At

an impressionable age, I learned that my parents were not gods—they are flawed

human beings. Watching my mother’s meltdown caused by my father’s infidelity, I

discovered the dire consequences of being emotionally dependent on a spouse. I

told myself back then that I would never want to be in her position. I would

never allow my love for a man to turn into ammunition that he could use to maim

me. I also learned the importance for a woman to be financially independent—with

no economic means, Mama could not leave Baba even if she wanted to. She was an

old-school, conventional Asian housewife who had never worked a day outside of

her home.

During

this dark time, I was overwhelmed and did not know how to process my conflicting

emotions. On the one hand, I was angry. How could Baba betray Mama when she

dedicated her whole life to us? At the same time, as a Daddy’s Girl, I was

confused. Baba was indulgent, showering me with his affection and bringing me

trinkets from his trips. When I needed help with my chemistry homework, he was

attentive and patient. He was also a fun-loving father who took me and Davis

snowboarding on the weekends. I knew he loved Davis and me, but his affair

broke Mama’s heart and spirit. I did not understand how such an amazing father could

be such a shitty husband.

I

developed unhealthy relationship patterns around this time—I worried about men

cheating on me or leaving me, but I also desperately dreaded being alone. My

strategy was to become infatuated with a person and charm him with

attention—the goal was to have him fall hopelessly in love with me, so he would

not cheat or leave. At the same time, because I never wanted to be dependent on

a man for my financial well-being, I moved around for my education and career. I

never stuck around for anybody.

On

the surface, I seemed accomplished and strong, but underneath, I was insecure

and lonely. The tough girl who smoked and defied her mother was just a façade. Since

having my first boyfriend at seventeen, I had not been single for more than a

few months at a time. Like a rabbit chased by an unknown assailant, I dashed

from one man to the next, looking for someone to validate me, to calm the

nagging, neurotic voice inside my head: I

would never find someone who would love me because I am always “too” something.

I am too fat. I am too emotional but also too ambitious. I am too crazy, too

free-spirited. I talk too fast, think too much, and has too many feelings. I am

too strong-willed, and at the same time, too needy. Over and over again,

this voice whispered to me throughout my relationships. With every failed

relationship, it confirmed that I was unlovable.

When

I met Gökhan, the nagging voice subsided. We connected on OkCupid and hit it

off. He was living in Copenhagen and seemed like a reliable and attentive man. He

was cute too, with wavy, dark brown hair, deep-set mahogany eyes, a straight

nose, and a thoughtful demeanor. He quieted my anxiety with his patient,

soothing voice. We fell asleep talking to each other on Skype many nights. I

felt safe having him in my life.

The

start of our relationship was a sweet and romantic internet fairy tale that

spanned continents. After chatting online for three months, we met in person in

Istanbul. On our second night together, Gökhan and I climbed several flights of

creaky stairs to reach the rooftop of one of the budget hotels in the Old City.

Opening the door to the terrace, the twilight before sunrise greeted us. Gökhan

draped a blanket around me when he saw me shivering in the chilly, pre-dawn

gust. Then, groping his way in the darkness, he led me to the shabby lounge on

the far side of the terrace. We shuffled in our flip-flops, trying to suppress

our giddiness. I looked up, enchanted by the constellation above me. As my gaze

followed the horizon, I saw the flickering white lights from the boats and

ferries dotting the Bosphorus, the strait that functions as a border between

Asia and Europe. The twilight was misty, making it hard to see where the sky

ended and the Bosphorus began. Over the railing of the terrace were the muted

shadows of the shops, homes, and hotels of Old City, peacefully asleep. All around

us, the shutters were drawn, the lights dimmed, and it was quiet. We sat bundled

up on the lounge in the blanket. I was snuggling up next to a man whom, days

before, I had only seen on a computer screen. He bent down and planted a kiss

on my lips.

“Allahu

akbar, Allahu akbar, Allahu akbar, Allahu akbar, Ash hadu an la ilaha illal lah…”

the muezzin called out the first

stanza of the haunting and melodic adhan

at the crack of dawn to remind all Muslims it was time for the opening prayer

of the day. My eyes flew open. To my surprise, my surroundings had transformed.

Twilight had receded, and in its place, the sun emerged. The first pink and

orange rays illuminated the sky, chasing away the stars. I rubbed my eyes as

the sunshine warmed my face inviting me to crawl out of the warmth of Gökhan’s

arms. At dawn, the Bosphorus was no longer shrouded in a mysterious mist– it

was bustling with ferries and ships moving back and forth between Asia and

Europe. The city below was no longer sleeping; it was buzzing with horns and

chatter as people arose from their beds to begin a new day. I was in awe of Istanbul’s

transformations between night and day. Looking at Gökhan’s handsome face on

this brand-new day, I kissed him before we headed back to our room. I was happy

and in love.

***

Less

than a year later, we faced a conundrum.

I followed Gökhan out of the room and closed

the door as his aunts and sisters giggled behind us. We entered the next room,

which was his parents’ bedroom and he sat me down on the edge of the bed.

Averting my quizzical eyes, Gökhan said, “When the imam asked me what your religion was, I couldn’t tell him that you

didn’t have one. So, I told him that you were a Buddhist. He said since you are

of the Book—neither Christian nor Jewish, you would need to convert.”

His words took a few moments to sink in. Once

I understood the gravity of the situation, I started to panic. Did he know this was going to happen before

talking me into the nikah?

“This

is not part of the deal,” I shouted, shaking my head. The pins keeping my

lavender headscarf in place pricked my scalp. “You promised that I didn’t have

to convert if I go through the nikah!”

I glared at him; my gaze was accusatory.

“I’m

sorry I didn’t know,” he muttered, “You don’t need to go through with it if you

don’t want to. It’s completely up to you.”

Is it up to me? No, it’s not up to me! I started to cry.

Gökhan looked at me with his thoughtful eyes. He handed me a tissue. I dabbed

my eyes, blew my nose, and shed more tears. I looked up and saw myself in his

mother’s vanity mirror. The rebellious teenager inside me mocked my puffy face

and smeared make-up—but I could not stop crying. Gökhan fidgeted next to me,

occasionally patting me on the shoulder and repeating the phrase, “You don’t

have to do this if you don’t want to.”

Don’t you

fucking understand? I shouted inside my head. From now on, we can never be truly happy

together. If I don’t convert, your mother is going to hate me forever, and I am

going to feel lousy making you choose between her and me. If I do convert, I

will resent you for as long as I live. I kept my head bowed because I could

not stand looking at the helpless expression on his face. I could not utter a

word because if I tried verbalized my feelings, I would start wailing. The teenaged

me would have walked out of the door without looking back. She was, however,

overpowered by the decent Taiwanese daughter who did not want her future

husband to lose face.

Looking

back, I realized that I put myself in this messy situation on an impulse and

deeply rooted fear. I was in love with the idea of being in love. I also loved

having an exotic boyfriend who had grown up in a set of cultures that were

vastly unlike mine. I bragged to friends that between the two of us, we had

four passports. At the same time, it was my fear of being alone that drove me

to this irrational decision to go through with nikah. Knowing what I know now, I should have walked away—coercion

and compromised integrity are not a good foundation for marriage. However, as a

third culture kid, I have been crossing borders and adapting to different

cultures my whole life. I thought I was ready to cross a new one with Gökhan.

I

was wrong.

I

wept for an eternity, shed enough tears to fill the Bosphorous. The girl with a

cigarette dangling between her fingers, dated white boys and covered herself in

tattoos had turned into Gökhan’s bewildered bride. On the other side of the

door, the imam was waiting for me to change my wicked, wayward ways and Gökhan’s

entire clan was expecting us to profess our undying love and commitment to each

other. I cried and cried like a lost child. I did not know how to get out of

this mess.

Out

of nowhere, Gökhan’s father walked into the room. He was smiling. He closed the door behind him and started laughing. I gave him a look of

bafflement as he spoke rapidly in Turkish. He paused and nodded his head.

Gökhan looked at me and interpreted what his father had said, “My dad said

you are taking this whole thing way too seriously.”

His

father grinned at me, said a few more words and nodded again. Gökhan

translated, “He said it’s totally fine if you don’t want to go through with it.

But you could also put on a show by pretending to convert, which would make

everybody happy.”

I

stared at his father, shocked that he had just asked me to go out there and

tell a lie in front of the whole family. He chuckled, nodded at Gökhan again

and left without saying another word. What his father wanted me to do was what

he had done, and what Gökhan had done his whole life: pretend and go through

the motions to make peace. I felt defeated and exhausted. I forced my gaze back

to Gökhan. Oh, what I would do just to

make this awful situation go away!

After taking a couple of deep breaths, I asked

Gökhan to fetch my makeup bag from the next room. I cleaned my face with fresh

tissue and wiped away the black smudge under my eyes. When Gökhan returned, I

smeared a thick layer of foundation and powdered my face. Then, I applied a

sparkly lilac eyeshadow that matched my lavender headscarf. Staring at my

reflection in the mirror, I grinned. My eyes were still puffy; my smile looked

pathetic but convincing enough to those who did not know me. I smiled again and

knew that my mask was secure. I reached for Gökhan’s hand and led him out of

the room.

Sadly,

Mama’s rebellious Canadian daughter did not have big enough guns to fight the

rebellion in Denmark. After all, I was only one young woman trying to keep my

integrity abreast in the face of a conservative, cultural tidal wave.

I

followed the imam, who told me to

repeat the Shahada, the Arabic script

that would declare me a Muslim. “La ilaha

illa Allah wa-Muhammad rasul Allah,” which translates to “I testify

that there is no other God but Allah, and Muhammad is God’s messenger.” The imam said it slowly, pausing after every

few syllables to allow time for me to mimic the foreign sounds. Afterward, I

signed a piece of paper that the imam

had prepared. Shortly after, he declared us husband and wife.

From

that day, I resented Gökhan. I never forgave him for putting me through a

conversion.

Our

union did not last long. Four months after we arrived in Bahrain, the Arab

Spring broke out. A series of protests swept across the Arab world. In Bahrain,

the government cracked down on the demonstrations, which created an environment

of fear and uncertainty. The turmoil made it difficult for Gökhan to find work.

A year and a half later, when he finally secured a job in Dubai, our marriage

crumbled. Instead of following him, I got a job in Hong Kong to be closer to my

parents in Taiwan. We broke up.

Many

years later, I found the lavender headscarf in my wardrobe. I am still in Hong

Kong, but now married to a wonderful man who loves and accepts me just the way

I am. Though painful, I learned so much from wearing the headscarf that day, like communicating expectations, and accepting the

people I love for who they are, instead of trying to change them. Even

though going through nikah and living in Bahrain was challenging, I would not trade

that experience for anything else. Without it, I would not have learned how to be in a

loving and equal partnership. Taking

one last look at the headscarf, I put it in the trash bin. I have come a long

way— the girl who smoked in the mall has grown up and learned how to love

herself. I now know that I am strong enough to be the person that I have

become.